Why Your Product Company is Just a Body Shop in a Hoodie: The Productivity Paradox

The boardroom at ZenithTech didn’t just smell like expensive espresso and desperation; it smelled like the collective anxiety of three hundred people trying to sprint through a swamp. Sanjay, the CEO, was vibrating with a specific kind of “Founders’ Anxiety” that usually precedes a catastrophic pivot or a very expensive divorce.

“We have a productivity problem,” Sanjay barked, pointing at a Jira board that looked like a digital representation of the fall of Saigon. “The European enterprise client says we aren’t shipping fast enough. Our ‘velocity’ is in the toilet. I’ve just greenlit a contract with a vendor to provide eighty ‘resources’ by Monday. We’re going to crush this backlog through sheer force of will.”

I looked at the lead architect, a man who had seen enough “agile transformations” to know they usually ended in a fetal position. “Sanjay,” he started, his voice a low gravel, “We don’t have a productivity problem. We have a skill mediocrity and inability to focus problem. You’re trying to solve a structural engineering issue by hiring more people to stand on the roof. It’s not just that they won’t help—the extra weight is going to make the whole building collapse. You’re confusing ‘doing more’ with ‘being productive.'”

Sanjay didn’t care about the laws of physics or the nuance of output. He cared about the optics of “scale.” He was about to learn that in a true product company, volume is often the enemy of value, and “busy” is the most expensive word in the English language.

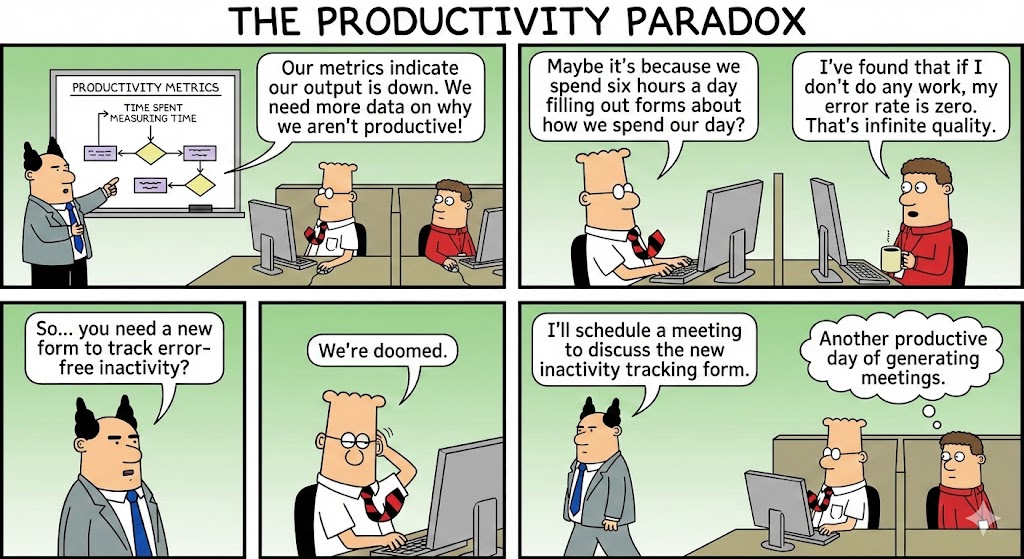

The Productivity Delusion: Measuring the Wrong Thing

In the tech world, productivity is the most misunderstood word since “disruption.” Most managers—especially those who cut their teeth in legacy service firms—measure productivity through the lens of activity. They track hours logged, tickets closed, and lines of code. This is the ultimate Optimism Bias. We assume that because everyone is moving, we must be going somewhere.

But as I’ve noted before, organizations should worry about optimism bias and structure its KPIs carefully. If your KPI is “number of features shipped,” your team will ship a hundred useless features that break the core product. You aren’t productive; you’re just a very efficient factory for technical debt.

True productivity in a product company is defined by Leverage.

“A manager’s output = The output of the units under his supervision + The output of the neighboring units under his influence.”

— Andy Grove, High Output Management

In a service company, leverage is low because revenue is tied to time. In a product company, leverage is everything. If you spend three months building a feature that ten million people use, your leverage is astronomical. If you spend those same three months building a custom dashboard for one client, you aren’t a product company. You’re a service firm with a very expensive hoodie.

Sherlock Economics and the “Body Shop” Virus

The fundamental tragedy of the modern startup is what I call Sherlock Economics: why your 20M AI startup is just an unpaid internship for OpenAI. When you build a company on someone else’s infrastructure and then hire a massive team to “service” the implementation, you have effectively turned into a body shop.

A body shop thrives on mediocrity. It needs “billable resources” who are competent enough to not get fired, but not so excellent that they automate themselves out of a job. In a service model, excellence is a margin killer. In a product company, that same engineer is a god.

This is where the Theory of Constraints from Eli Goldratt’s The Goal kicks in. In any system, there is one bottleneck. At ZenithTech, the bottleneck wasn’t the code; it was the “People-Process.” Every time Sanjay promised a custom feature to “increase productivity,” he created a new bottleneck. When you “throw people” at a problem, you aren’t widening the bottleneck; you’re adding more water to the funnel. You create “Coordination Headwind.”

The Math of the “Rockstar”: Why 1 > 5

There is a pervasive belief that five average engineers are better than one great one. The data tells a different story. A study by Hunter, Schmidt, and Judiesch found that in high-complexity jobs, the top 1% are 127% more productive than average performers.

When you hire five mediocre engineers, you don’t increase productivity; you increase communication friction:

- 1 Engineer: 0 communication paths.

- 5 Engineers: 10 communication paths.

- 50 Engineers (Sanjay’s dream): 1,225 communication paths.

The “Communication Overhead” grows at a square of the headcount. This is why good products fail despite having best engineering and process teams. Hiring one great engineer at 3x the salary is the most “lean” strategic move you can make. They write cleaner code and don’t require a “Scrum Master” to tell them how to breathe.

Hire Slow, Fire Fast: Why Baggage is a Slow Death

Hiring as a defensive measure is the “Sanjay Special.” In a product company, a mediocre hire is a toxic asset. They act as a Productivity Tax on your best people. Every time a great engineer has to fix a sloppy bug or sit through an “alignment meeting” for someone who doesn’t get the architecture, your company’s leverage drops.

Hiring Slow is about protecting “Talent Density.” If you aren’t 100% sure, the answer is no. A hole in your headcount is better than a hole in your culture.

Firing Fast is the part everyone hates because it feels “mean.” But keeping a mediocre performer—the “Baggage”—is a slow death:

- The Resentment Loop: Your A-players see the B-player getting the same salary while doing 10% of the work. They eventually leave.

- The Bozo Explosion: As Steve Jobs noted, B-players hire C-players because they don’t want to be challenged. Soon, your company is just a massive bureaucracy where no one remembers how to build anything.

“Adequate performance gets a generous severance package.”

— Netflix Culture Deck

If you don’t prune the garden, the weeds will choke the roses. It’s not about being ruthless; it’s about being compassionate to the people who actually drive value.

The Behavioral Science of the “Death March”

Why do we keep hiring more people to solve a “productivity problem”? Because we are slaves to our own biology. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s work on Loss Aversion explains that the pain of losing a client is twice as powerful as the joy of building a great product.

Managers say “Yes” to custom requests to avoid “loss,” then fall victim to the Planning Fallacy—the irrational belief that “this time, it will only take a week.” It never does. This leads to the “Death March”—twelve-hour workdays that look productive but are actually the graveyard of quality.

Richard Thaler’s Nudge Theory shows that if you reward “Face Time,” people will stay until 10 PM. But human cognitive output is a bell curve. Code written in the tenth hour is dangerous. Productivity isn’t about the number of hours your eyes are open; it’s about the quality of the decisions made while they are. Productivity is about Ruthless Execution. As I’ve said, it is the blood sport of ruthless execution and the strategy of saying no.

The Culture Map: Why Your “Operating System” is Crashing

In my 25 years working across the US, UK, France, India, Israel, China, and SE Asia, I’ve realized that culture is the invisible code. If the OS is buggy, the apps (employees) won’t run. To understand why productivity fluctuates globally, we look at Erin Meyer’s The Culture Map.

The Feedback Loop: Direct vs. Indirect

In France or Israel, if your code is bad, someone will tell you it’s “rubbish” to your face. It’s brutal but efficient. In the US, they use the “Feedback Sandwich.” In many Asian cultures (India, Malaysia, Singapore), giving direct negative feedback is “losing face.”

- The Productivity Bug: In a product company, you need “Creative Friction.” If the engineers are too polite to tell the VP his architecture is a disaster, you will spend $2M building a disaster.

The Power Distance: Egalitarian vs. Hierarchical

In Denmark or the US, a junior dev can argue with the CTO. In India or China, the HIPPO (Highest Paid Person’s Opinion) is the law.

- The Productivity Bug: If you treat your product company like a hierarchy, you lose the “Distributed Intelligence” of your team. Productivity dies when 500 people are waiting for one person to tell them what to do.

Persuading: Principles-First vs. Applications-First

French engineers often want to understand the “Why” and the theory before they write a line of code (Principles-First). Americans just want to see a working prototype (Applications-First).

- The Productivity Bug: This leads to massive friction. The US manager thinks the French dev is “slow,” while the French dev thinks the US manager is “reckless.”

The Financial Truth: Revenue Per Employee

The ultimate metric of productivity isn’t in Jira; it’s in the annual report. Look at Revenue Per Employee (RPE) and ROCE (Return on Capital Employed).

- Apple/Google: ~$1.5M - $2.4M per employee. This is pure leverage.

- Service Firms: ~$60,000 - $80,000 per employee. This is a body shop.

The gap is “Leverage.” When your RPE is low, your PE ratio follows. Investors know that if you need 10,000 people to generate $1B, you have no leverage. You aren’t selling a product; you’re selling meat. If your “Product” company has an RPE closer to an accounting firm than a tech titan, you aren’t scaling—you’re just getting fat.

To stay productive, you must follow the Netflix “Keeper Test”: “If this person wanted to leave, would I fight to keep them?” If the answer is no, give them a generous severance. Keeping a mediocre performer is a “productivity tax” on your high-performers. Hire slow, fire fast.

The Productivity Litmus Test: 10 Brutal Questions for Company Leadership

If you’ve reached the point where you’re asking these questions, you likely already know the answer. You’re sitting in a “Product” office, but the air smells like a billable-hours sweatshop.

To help you confirm your suspicions—or to give you the ammunition you need to stage a boardroom intervention—here is the Brutally Honest Productivity Health Check.

1. The Revenue-to-Meat Ratio

“If we doubled our revenue tomorrow, would we be forced to double our headcount to support it?"

The Logic: This is the ultimate test of Operating Leverage. If your revenue and headcount move in a 1:1 ratio, you aren’t a product company; you’re a body shop in a hoodie. High productivity means your code does the heavy lifting, not your recruiting team.

2. The “No” Audit

“What was the last high-value feature request from a major client that we said ‘No’ to because it didn’t align with our product roadmap?"

The Logic: As I’ve written in the blood sport of ruthless execution, strategy is about sacrifice. If you say “Yes” to every custom request, you are a service firm doing “Unpaid Internships” for your clients’ edge cases.

3. The 10x Math

“Would we rather hire one ‘Rockstar’ engineer for 3x the market rate or five ‘Average’ engineers at the standard rate?"

The Logic: If the answer is the latter, your leadership doesn’t understand Brooks’ Law or the exponential cost of communication overhead. They are optimizing for “Shovels” instead of “Cathedrals.”

4. The Keeper Test

“If our ‘adequate’ performers resigned today, would we fight to keep them, or would we be secretly relieved to use that budget on an A-player?"

The Logic: Keeping mediocrity is a “Productivity Tax” on your best talent. As Andy Grove noted, a manager’s output is the output of their unit. If you’re harboring baggage, you’re intentionally lowering your unit’s output.

5. The HIPPO vs. The Data

“When was the last time a junior engineer successfully challenged a technical decision made by a VP or the CEO?"

The Logic: Referencing The Culture Map, high-power-distance cultures kill innovation. If the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion is the only one that matters, your productivity is capped by the intelligence of one person instead of the collective brainpower of the team.

6. The “Busy-ness” Metric

“Do we measure success by ‘Features Shipped’ and ‘Hours Logged,’ or by ‘Outcome-Based Value’ and ‘Revenue Per Employee’?"

The Logic: Measuring activity instead of outcome is a classic case of Optimism Bias. You can be incredibly “busy” digging a hole in the wrong place. Productivity is about the depth of the hole, not the speed of the shovel.

7. The Customization Trap

“What percentage of our engineering time is spent on ‘General Product’ vs. ‘Client-Specific Hacks’?"

The Logic: If more than 20% of your time goes to custom work, you are a consultancy. You are effectively charging for hours while pretending to build an asset. This is Sherlock Economics at its worst.

8. The Automation Benchpress

“If we automated the manual tasks currently handled by our ‘Operations’ or ‘Success’ teams, how many people would we actually need to let go?"

The Logic: Product companies automate until it hurts. Service companies hire “Gary in the basement” to run manual CSV exports because Gary is cheaper than a developer’s time today. This is a slow-motion suicide for your ROCE.

9. The Feedback Sanity Check

“Do our engineers feel safe enough to tell leadership that a deadline is ‘Logically Impossible’ without being told to ‘just hustle harder’?"

The Logic: This is where Daniel Kahneman’s Planning Fallacy meets the real world. If you ignore the laws of physics, you get a “Death March.” A Death March is the scheduled destruction of your talent’s productivity.

10. The Ultimate Truth

“If our company was judged solely on our ‘Revenue Per Employee’ compared to a top-tier tech firm, are we a tech giant or a call center?"

The Logic: Numbers don’t lie. If your RPE is under $150k, you are a service business. Own it, or fix it.

The Verdict:

- 0-3 “Yes” Answers: You are a pure Product Company. Stay lean, stay ruthless.

- 4-7 “Yes” Answers: You are in the “Danger Zone.” You’re a product company that’s slowly being eaten by the “Service Virus.”

- 8-10 “Yes” Answers: Congratulations, you work at a body shop. Update your LinkedIn and find a company that actually values leverage.

The Closing of the Loop

Back at ZenithTech, the eighty “resources” arrived. They were lovely people, but they had no idea how our core architecture worked. Because the culture was hierarchical and “face-saving,” they never told Sanjay they were lost. They just kept quiet and moved tickets around in Jira to look busy.

The senior engineers—the ones who actually built the product—spent 90% of their time in “Onboarding Sessions” and “Code Reviews” that felt more like basic literacy classes. Our “Velocity” went negative. We were actually losing features because the new guys kept overwriting core logic.

Sanjay was ecstatic. He showed the board a chart showing “Headcount Growth” as a proxy for “Productivity Growth.”

Three months later, the European client canceled the contract. The software was too buggy to deploy. ZenithTech’s RPE plummeted, and the “Product” was now a “Service Monster” that required 400 people to keep the login screen from crashing.

The tragedy of modern tech is that we’ve forgotten what productivity looks like. It doesn’t look like a crowded office or a long Jira board. It looks like a small, quiet room where three brilliant people are saying “No” to a hundred bad ideas so they can say “Yes” to the one that changes the world.

Stop counting the shovels.